Traits of an Effective Sponsor in the Adult Catechumenate

Last week Kent introduced the topic of sponsors in the adult catechumenate, focusing on ways in which sponsors “are one of the direct links to the life of the congregation and all its members.” Sponsors are described as companions who mentor, coach, and guide those in the adult faith formation process.

This week we look at the essential traits of a sponsor, again drawing on the Roman Catholic resource Guide for Sponsors by Ronald J. Lewinski (4th edition; Liturgy Training Publications, 2008). Written for sponsors, the book uses second person discourse frequently, speaking directly to potential and actual sponsors. Chapter 4 lists six traits that a sponsor “should strive to develop,” describing each in a few paragraphs:

- A sponsor prays. As first on the list, an active prayer life is implicitly lifted up as the most important trait of a sponsor. To be a sponsor may “inspire you to deepen your prayer life” (21). The guide lists “sources” of prayer, naming first Scripture, especially the Sunday lectionary (assumed to be the primary source of the catechetical teaching), and the psalms, steeped in “the very experiences of life.” Group prayer and developing a level of comfort with “spontaneous prayer” are also encouraged (21-23).

- A sponsor listens. Sponsors are cautioned to rein in their excitement about their faith. Lewinski writes that it’s “imperative that we commit ourselves to listen with respect …” and help the catechumen or candidate feel comfortable asking questions (24).

- A sponsor is respectful. Respecting the candidate or catechumen is a thread running through this chapter, but here Lewinski expands further, saying that sponsors need “also to honor what they hear” (25). To close this section he writes, “A sponsor’s understanding of and respect for a person’s ethic background, cultural heritage, values, and beliefs are the foundation for communication and productive relationship” (26).

- A sponsor serves as a bridge. The sponsor is a bridge both to the people of the parish as well as its “customs and practices” (27). The author recommends accompanying the candidate or catechumen to liturgies and other parish activities and encouraging questions about their experiences.

- A sponsor respects the candidate’s freedom. “A sponsor can hold on too tightly” writes the author to begin the discussion of this trait. The emphasis here is on the delicate balance between a warm, inviting welcome and allowing candidates the freedom “to depart without feeling they will offend us” (28). The balance is especially important in the early stage of inquiry and when a sponsor is a relative or close friend of the candidate or catechumen. Lewinski notes that this freedom “is easier to give when you are secure in your life as a Catholic” (29). The same would be true of any Christian tradition.

- A sponsor lives in the world with hope. This “spiritual process,” say Lewinski, has as its goal “to prepare men and women for living in the world as disciples of Jesus,” as Christians “confident in their ability to live their faith in the modern world” (29). The abiding hope of the sponsor models for the candidate or catechumen ways of daily living in a world with values that are at odds with the Christian faith.

The chapter concludes: “Together with the one you sponsor, trust in the guidance of the Holy Spirit and walk confidently on the path of faith that lies before you” (30). Our goal with this two-part series is to introduce to our readers this Roman Catholic resource and its adaptability for adult faith formation in Lutheran and other Protestant congregations. We would not recommend that sponsors read the book with its many specific references to the Roman Catholic tradition, but it could be an excellent resource for pastors as you recruit and train sponsors.

++++++

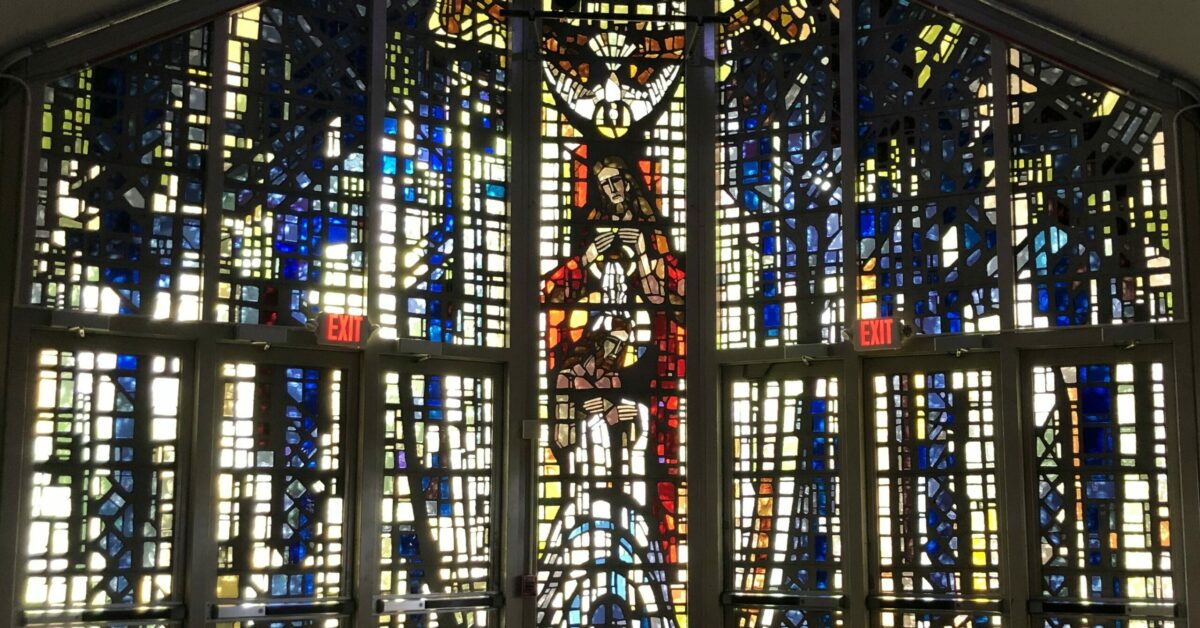

Banner image: The baptism of Jesus by John, northeast entrance to Chapel of the Holy Trinity, Concordia University, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Photo by Rhoda Schuler (CUAA, ’75 [AA degree]), June 2024.