OCIA: Prayers of the Third Scrutiny (revised)

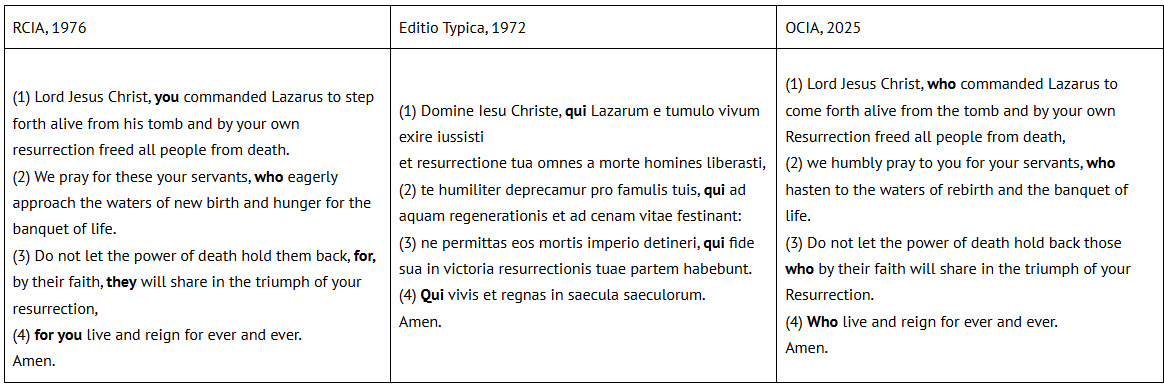

Our nerdy journey into the new (yet retro) translation of the OCIA texts for the Scrutinies takes a divergent path this week (into the Latin original for comparison). A few reminders: These texts draw on the Gospel readings in Lent for Year A (Lent 3, 4, 5), all from the Gospel of John, all terrific narratives: the woman at the well, the man born blind, and (today’s subject) the raising of Lazarus. Each set of texts for a given liturgy includes prayers (a lead collect and prayer of exorcism, as Kent noted last week), for which there are two options. To illustrate my primary points this week, I’ve chosen the prayer of exorcism, Option B, and this week I took the time to find the Editio Typica, the official Latin text. Here we can see clearly the principle of formal correspondence at work in the recent OCIA translation, which “is not so much a work of creative innovation as it is of rendering the original texts faithfully and accurately into the vernacular language” (Liturgiam Authenticam, 49). As Kent asked in his March 6 post, “Or do they achieve their own goal according to Liturgiam Authenticam of providing ‘language which is easily understandable, yet at the same time preserves these texts’ dignity, beauty, and doctrinal precision?’” (Liturgiam Authenticam, 25).

First, look at the OCIA translation, the third column, and note the word in bold in each of the four sections of the prayer: “who ….” Then move to the middle column and see the bold word in the original Latin: “qui ….” The Latin text is laden with a relative clause in each section, all of which are retained in the OCIA translation, a clear example of the principle of formal correspondence at work. Note that the RCIA drops two of the relative clauses (in sections 1 and 3), likely to break up the prayer for an aural reading, in a way that, one might argue, uses “language which is easily understandable, yet at the same time preserves these texts’ dignity, beauty, and doctrinal precision.” In contrast to the prayers Kent analyzed last week, the translations are very close.

- As noted, the “who” (qui) is abandoned for “he” in the RCIA translation, allowing for the statement of Christ’s work to end with a period—a pause for the assembly to connect this prayer with the Gospel text. The only other difference is the infinitive (exire). The OCIA (to come forth) is an example “of rendering the original texts faithfully and accurately,” while the RCIA, “to step forth,” is more vivid and concrete, emphasizing the human agency of Lazarus. Note also that this prayer of exorcism is addressed to Jesus, the One who overcame temptation by the Devil and who cast out demons.

- One need not be fluent in Latin to notice that the OCIA includes the Latin modifier “humbly,” while the RCIA omits the word, leading to speculation about the motives of scholars translating in the 1970s. Perhaps they felt it drew attention to those “humbly” praying at the expense of those for whom the prayer was offered, the Elect preparing for baptism. One can be more confident speculating about the reason for the RCIA addition of a second verb in the relative clause. In the OCIA version, the servants are hastening to both baptism and the Eucharist. But the RCIA not only translates the verb in more common vernacular (“eagerly approach”), but the translators also deliberately chose to include the word “hunger,” rendering the phrase “and hunger for the banquet of life.” As with the verb in section 1, “hunger” is more concrete, with an obvious connection to “the banquet.” “Hunger” evokes a physical sensation universally known, but here used with a spiritual meaning.

- Here is the heart of the petition, of the exorcism; the wording in the two translations is identical with the exception of the rendering of the relative clause. The OCIA’s translation is faithful and accurate: “Do not let the power of death hold back those who by their faith ….” What of the RCIA? “Do not let the power of death hold them back, for, by their faith, they …” The OCIA seems very straightforward—so much so that it seems “the servants” for whom this prayer is offered don’t really need our prayers. The RCIA wording implies that the power of death may impede their faith, and the prayer implicitly asks that their faith remain strong.

- Here the RCIA, by replacing “who” with “you” makes clear that this phrase is addressed to Jesus, not to those for whom the prayer is offered.

The liturgy calls for poetic language evocative of the human experience. To step forth … to hunger … these word choices bring concrete actions and feelings to the ambiguity of spiritual formation. While they may fail the text of formal correspondence, they are words of dignity and beauty.

+++

Banner photo “The Tomb of Lazarus” by Breen, A. E. (Andrew Edward) – A diary of my life in the Holy Land. J. P. Smith printing company Rochester, N.Y., (1906), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6771086

For the main text, see page 65-66, par. 178

For the Option B prayers, see page159-60, par. 378