Enlightenment during Advent: Repentance and Healing

A full and robust catechumenal process has four stages: inquiry, catechesis, enlightenment or final preparation (which culminates with the sacrament of baptism or a rite of remembrance/renewal for those already baptized) and mystagogy. Our current Advent Series is exploring an alternative timing of the catechumenal process. We are taking a close look at the lectionary readings leading up the festival of the Baptism of our Lord, as a suitable time for the final preparation or stage of Enlightenment. Last week Kent’s blog reviewed the final two weeks of the church year, noting the themes from the appointed gospel texts in the lectionary that correlate with themes of discipleship for this stage of the catechumenal process.

Today we flip the calendar (and lectionary year) to the first Sunday of Advent (Year A, with Matthean gospel texts). In the Roman Catholic catechumenal process, these Sundays include “the scrutinies,” which are “rites for self-searching and repentance … meant to uncover, then heal all that is weak, defective, or sinful in the hearts of the elect” (Catholic Rites Today, 91-92). The corresponding ecumenical Journey to Baptismal Living rites of “Healing and Deliverance” have a similar purpose (and a more eponymous title). As Kent noted, our starting point is the LSB lectionary, which is closely aligned with the Revised Common Lectionary (RLC). For Advent 1, the two lectionaries are nearly identical, and themes appropriate for this third week in the stage of Enlightenment run as a golden thread through all the appointed texts.

The Advent 1 Old Testament reading, Isaiah 2:1-5, is filled with beautiful language of “all nations” that “stream to [the Lord’s house]” (2:1). The people of all nations are quoted: “Come … [so that the Lord] may teach us his ways and that we may walk in his paths” (3). The Lord’s house, the temple in Jerusalem, is located on “the highest of the mountains” and the verb “to stream” evokes the image of moving water. Contrary to the natural world, where water flows downhill, the nations (in Isaiah’s day the enemies of the people of God) are streaming uphill—going against the flow of worldly life—and are drawn to the ways and paths of God. The text lends itself to the stage of Enlightenment, to the movement away from sin that separates people from God and toward a repentance heart, ready to listen to “instruction … out of Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem” (3). God’s judgment has the power to “beat their swords in plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks” (4), to end conflict and war. The text concludes with an exhortation to the people of Israel to do the same as “the nations”: “O house of Jacob, come, let us walk in the light of the Lord!” (verse 5).

That final phrase, “walk in the light,” is the image picked up in the epistle reading from Romans:

Besides this, you know what time it is, how it is now the moment for you to wake from sleep. For salvation is nearer to us now than when we became believers; the night is far gone, the day is near. Let us then lay aside the works of darkness and put on the armor of light; let us live honorably as in the day, not in reveling and drunkenness, not in debauchery and licentiousness, not in quarrelling and jealousy. Instead, put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires. Romans 13:11-14

Quoting again from the RCIA explanatory notes for the scrutinties, this is a most suitable text “for self-searching and repentance … meant to uncover … all that is weak, defective, or sinful in the hearts of the elect,” and to prepare them to “put on the Lord Jesus Christ” in baptism.

The traditional gospel text from the one-year lectionary, Jesus’ entry in Jerusalem (Matt 21:1-11), is list as the first of two options for Advent 1 in the LSB lectionary; the alternate LSB gospel text is the text appointed in the RCL, Matthew 24:36-44. Contextually, this latter passage is part of the eschatological discourse of Jesus spoken to his disciples who “came to him privately, saying, ‘Tell us, when will this be, and what will be the sign of your coming of the end of the age?’’’ (Matt 24:3). The appointed text primarily answers the “when” question: “About that day and hour no one knows, neither the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father” (24:36). It will be “as the days of Noah were,” unexpected to many people; and as Noah was saved, so will some be at the “coming of the Son of Man” (24:37): one of two working in the field; one of two women grinding meal together (24:40-41). “Keep awake,” Jesus warns, and “be ready” (24:42, 43), language that evokes the same theme Paul wrote to the Romans: “now [is] the moment for you to wake from sleep. For salvation is nearer to us now than when we became believers; the night is far gone, the day is near” (11). These texts speak to the Elect in these weeks of final preparation, reminding them that baptism is not an end but a beginning, one that calls disciples to stay alert to the temptations of the world, to stay on the paths of the Lord, to hold fast to Jesus Christ, the incarnate Word, to “keep awake” so that they are prepared for his Second Coming.

Finally, we consider Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem and the question it evoked (Matt 21:10). “When he entered Jerusalem, the whole city was in turmoil, asking, ‘Who is this?’” The text has given clues, by quoting from Zechariah, “Look, your king is coming to you,” and by recording the shouts of the crowds: “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord!” This text may evoke for the Elect how they felt during the first stage of the catechumenal process, inquiry; perhaps some were “in turmoil” and asking “Who is this” about Jesus. The Elect (and the whole assembly) can be reminded on this Sunday of who Jesus is, the Word made flesh who lives among us and whose birth is anticipated with hope in this season of Advent.

To complete the circle, we return to Isaiah 2, filled with the powerful symbolism of the city of Jerusalem, from which comes instruction, and with the “house of the Lord,” the dwelling place of God. As Jesus enters Jerusalem, it’s Passover, and Jews from all over the Roman Empire have streamed to the holy city; they long for a king who will bring the peace of the pruning hook and plowshare—of agricultural abundance, not of the Pax Romani, maintained by the sword. Enter Jesus, who comes as a gentle king, who, if one reads further in Matthew 21, is healing “the blind and the lame” in the temple (21:14). It is this Jesus who comes to the Elect on this day to “heal all that is weak, defective, or sinful in the [their] hearts.”

+++++

Sources Referenced

Catholic Rites Today: Abridged Texts for Students, edited by Allan Bouley. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1992.

https://journeytobaptism.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2021/04/Rites-Booklet-2024-07021745.pdf

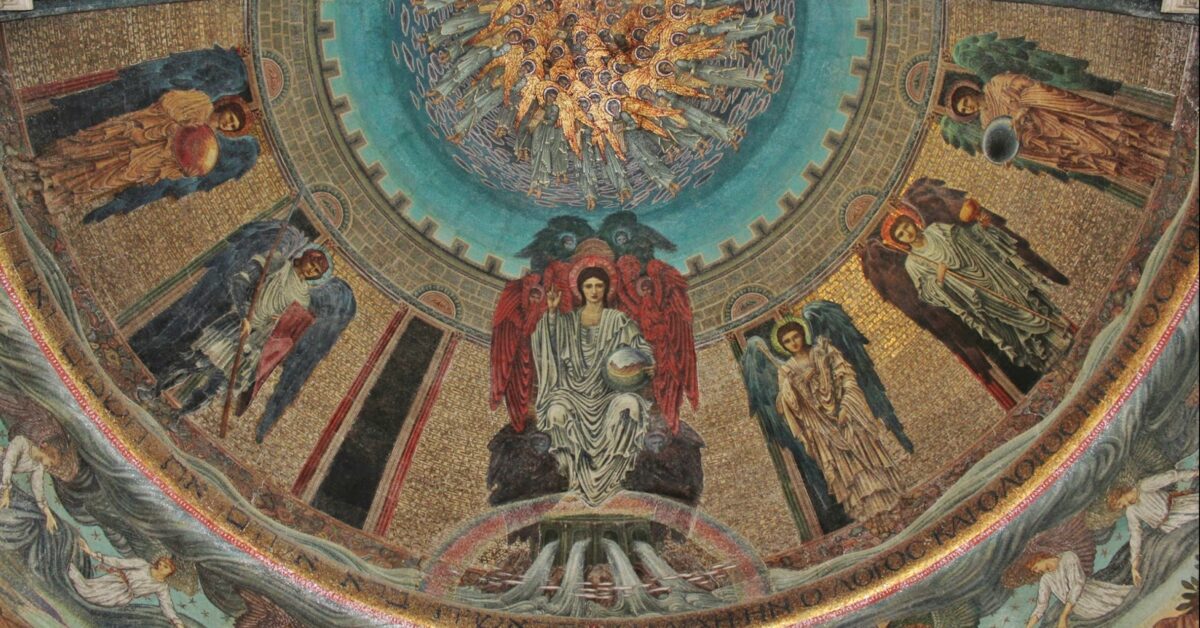

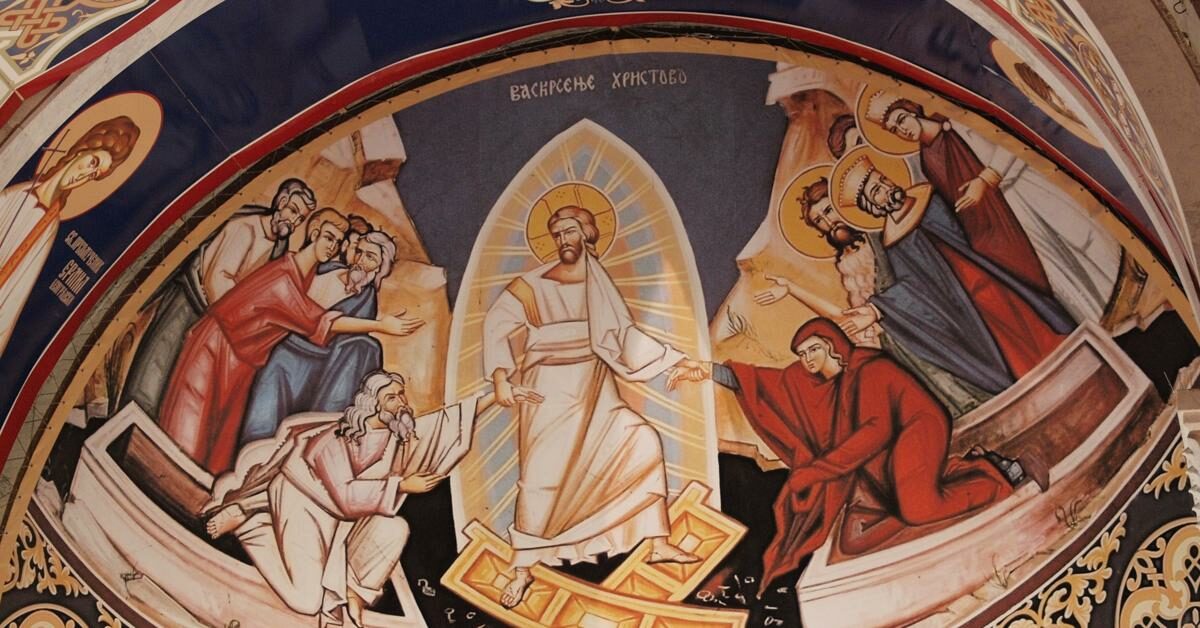

Banner Photo

Christ Enthroned in the Heavenly Jerusalem: Christ is flanked by archangels, with an empty space representing Lucifer’s vacated position. From left to right, the five archangels are: Uriel holds the sun; Michael is a glorious figure in armour; Gabriel bears the lily of the Annunciation; Chemuel (Camael), the angel of the Sangreal, stands next him with the sacred cup; and Zophiel (Jophiel), to his left, holds the moon. Mosaic at the St Paul’s Within the Walls, an Episcopal church in Rome, Italy, 1885.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Christ_Enthroned_in_the_Heavenly_Jerusalem,_St_Paul%27s.jpg

http://romananglican.blogspot.com/2014/09/st-pauls-within-walls-episcopal-church.html