Celebrating the Twelve Days of Christmas

Although it is (apparently) an urban legend that the origin of the carol “The Twelve Days of Christmas” stems from a time when Roman Catholics in England (16th to early 19th centuries) were not allowed to practice their faith openly, we’re featuring the modern legend on today’s post. The carol was purportedly written as a catechumenal song to teach youth Catholics about their faith, with each gift holding the hidden meaning of a Christian truth. As critics have pointed out, the 12 “hidden meanings” are shared by Christians across denominational boundaries; there is nothing distinctive to Roman Catholicism in them, and the hypothesis is rather recent. Nevertheless, I find the “hidden meanings” a lovely way to christianize an otherwise secular “carol,” especially since the celebration of Christmas by those for whom it is a secular and cultural holiday ends on “the second day of Christmas.”

Here are the 12 hidden meanings:

- The Partridge in the pear tree is Jesus Christ.

- Two turtle doves are the Old and New Testaments.

- Three French hens stand for faith, hope, and love.

- The four calling birds are the four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

- The five golden rings recall the Torah or law, the first five books of the Old Testament.

- The six geese a-laying stand for the six days of creation.

- Seven swans a-swimming represent the sevenfold gifts of the Holy Spirit: prophesy, serving, teaching, exhortation, contribution, leadership, and mercy.

- The eight maids a-milking are the eight beatitudes.

- The nine ladies dancing are the nine fruits of the Holy Spirit: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.

- The ten lords a-leaping are the ten commandments.

- Eleven pipers piping stand for the eleven faithful disciples.

- Twelve drummers drumming symbolize the twelve points of belief in the Apostles’ Creed.

This list could be a great way to teach some basics of the faith to both children and adults in a fun and festive atmosphere, perhaps as a Bible class or Sunday School lesson in early January (during the 12 days).

++++

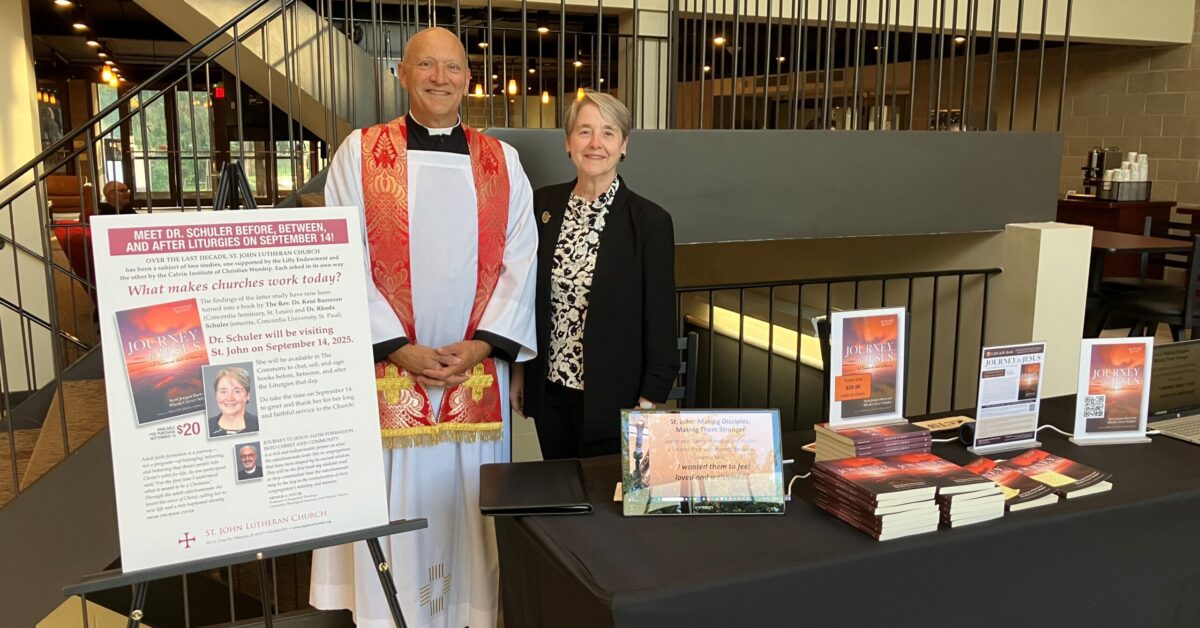

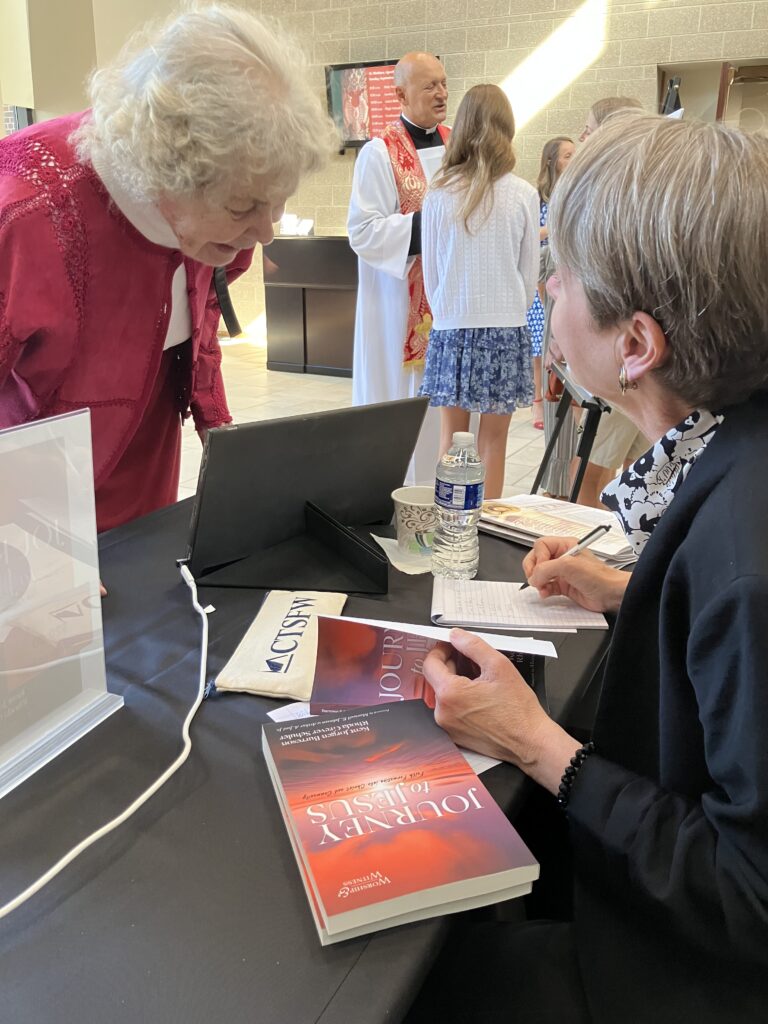

Banner image: Photo by Rhoda Schuler, 2026

Sources consulted about the “hidden meaning” of the carol:

https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/twelve-days-christmas

https://www.ncregister.com/blog/the-hidden-meaning-of-the-gifts-in-12-days-of-christmas

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Twelve_Days_of_Christmas_(song)#History_and_meaning